An affordable home gave Marsha Cutting peace of mind because even tireless community activists need a place to rest, especially later in life.

“I sailed into Eagle Harbor on November first of 2012,” recalls Marsha Cutting, 75. She had left her home in upstate New York to be closer to family and to escape the harsh winters, a particular hazard for someone who uses a wheelchair much of the time. It was a fitting arrival for a woman whose career and activism have been marked by courage and clear direction.

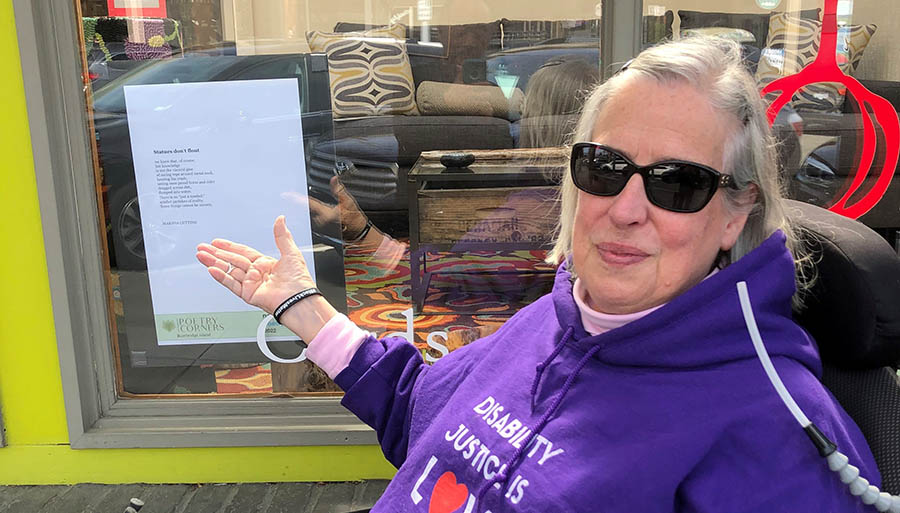

In New York, Marsha had served six years as a minister of a Presbyterian congregation and 15 as a chaplain at a psychiatric hospital. In her early 50s, she went back to school to earn a doctoral degree in psychology and embarked on a second career, first teaching, and later doing clinical work with an emphasis on psychological assessment. Today, retired from work but not from the causes she believes in, Marsha chairs the Kitsap County Accessible Communities Advisory Committee and serves on the Governor’s Committee for Disability Issues and Employment. She has been a member of the Multicultural Advisory Committee, which guides Bainbridge schools in creating an inclusive and informed school community, and is active in the local chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice.

The Pearson 26 sailboat, docked in the well-protected harbor at Winslow Wharf, would be her home for the next two years. Marsha had sailed it from Lake Champlain to Lake Michigan. From there, she had it trucked 2000 miles to Bainbridge Island. Critical details fell into place: a slip for the boat close to the ramp and a parking spot nearby. She could negotiate these short distances with a crutch and used her car to store and charge her motorized wheelchair. During her first summer, she set sail for five months, her small, slow boat taking her as far north as the tip of Vancouver Island, visiting Alert Bay and the Broughton Archipelago. But she was vulnerable. When a car accident left her with an injured shoulder (fortunately, not the one she used for her crutch), she decided to move ashore. “I wanted to make a transition at a time of my choosing rather than in the middle of a crisis.”

Marsha sold her boat and moved to a 350-square-foot apartment which fit her budget, but the bathtub proved an accessibility challenge and an elevated threshold at the entrance would catch the wheels of her chair. Two years later, she recounts, “I got hit with a 26% rent increase, and of course, no one had increased my social security or my pension.” And so at the age of 68, Marsha went back to work, performing psychological assessments for applicants to the ministry. But this too was not sustainable. She knew that with another rent hike, she’d either have to “work until [she] dropped” or leave Bainbridge Island altogether. “At my age I can’t keep moving,” she says, looking back at her predicament.

In October 2019, an ADA-accessible unit at HRB’s Ferncliff Village became available, and Marsha moved in with the help of many friends, just before the pandemic hit. By then she was experiencing increased health challenges, and with her housing costs now fixed and manageable, she was relieved to be able to retire—again.

She was also relieved to spend the pandemic not in the troublesome 350-square foot apartment but in a fully accessible home. “It may be that my favorite thing is the view as I look out at the gardens,” she adds, recalling the view of a “blank, gray wall” from her old apartment. “Here, there’s a little space between some of the trees where I can see the sound.” Some days she can see Mt. Rainier from the parking lot.

Marsha thinks a lot about aging, both her own and that of the community. Like many of her peers, she wants to age in place, which necessitates that she consider her own mortality. Will death arrive suddenly, she wonders aloud, or after a period of decline? She sees her friends struggle to find qualified home health aides, so many of whom travel to the island from less expensive homes as far as Bremerton, passing multiple places of work closer to home. And she anticipates how the lack of affordable housing will continue to affect her despite her newfound housing security.

Marsha was drawn to Bainbridge for more than the harbor’s calm waters, but for the welcoming liveaboard community on Bainbridge she had heard about. Life on the island proved equally so. Her move to the apartment coincided with Trump’s election and her political organizing, including a candlelight vigil at the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, would further bind her to the Bainbridge community. “I like the fact that it’s a small enough community that you make stuff happen,” she says. Marsha’s still making stuff happen, but she’s doing it from the safety and comfort of her home base, knowing that this is it for her. No more cross-country moves. No more sailing adventures. Just the peace of mind that comes from knowing when one has finally found a place to moor.